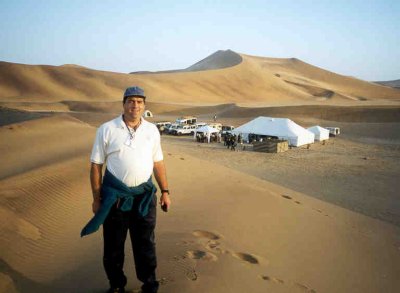

ERSA Conference Group

Namib Desert in Background

Evening Barbeque in the Dunes Sponsored by Namwater - the local Water Utility

Namibian Notes by Ted Gillespie, CWWA President.

I had the enormous privilege in October 1999, of attending, with Duncan Ellison our Executive Director, a workshop of the Eastern and Southern Africa Region (ESAR) of the International Water Association (IWA) in Swakopmund, Namibia. The travel, supported by the project described in the article CWWA has African Twins, provided the opportunity of cementing the development of the three proposed water and wastewater Associations with the IWA ESAR in order to have a greater assurance of post-project sustainability.

|

|

|

|

ERSA Conference Group Namib Desert in Background |

Evening Barbeque in the Dunes Sponsored by Namwater - the local Water Utility |

Namibia is a desert country with an annual average rainfall of 250mm (not much less than Southern Alberta), but their rainfall tends to happen all at once. The Country has several inland rivers, but they are dry most of the season. The Swakopmund river is dry most of the year, and only once in the last hundred years has there been enough flow to actually reach the ocean. Most times the river water is absorbed into the sand. Any open water disappears fast with the annual evaporation rate of more than 3 meters. The only natural vegetation is in the river beds where the plant roots can intercept the groundwater.

|

|

|

|

Typical Desert - Crusty Surface like Gravel |

Namib Dunes - about 5km outside of Swakopmund Some of the oldest and highest in the world. |

The town of Swakopmund has a population of about 25,000 people and is located on the Skeleton Coast in the middle of the Namib Desert. Water consumption in Swakopmund is about the same as in Canada, as is the price they pay for water service. Swakopmund shares a water system with neighbouring Walvis Bay. They have a series of wells and reservoirs distributed in an area within about 100km. The system is not sustaining as the aquifer is being drawn down at about double the rate of recharge. A desalinisation plant is planned to supplement supply so that aquifer levels can be replenished and sustained. Proposals to design/build/operate the plant were being reviewed during our visit.

Treated Waste Water in both Swakopmund and neighbouring Walvis Bay is used to irrigate municipal parks and boulevards, so the communities are quite ‘green’ considering the climate. Walvis Bay is considering providing treated wastewater to residents for irrigation, on a metered, fee for service, basis.

Swakupmund is a beautiful city with friendly people and many services. I would love to go back with my family for a holiday.

|

|

|

|

Typical Well Head in Desert River Valley There is a tap for local people to help themselves to water free of charge. |

Water Transmission Main - Environmentally Friendly because it keeps the 4x4's out of the desert. |

Listening to and participating in the discussions of the ESAR members who represented nations from most of continental southern Africa as well as from Madagascar in the Indian Ocean, provided me with a new perspective on water supply and water service. In many ways, the conditions of water supply in the large African urban centres are no different from our own - individual supply of potable water to a largely middle class population. Throughout most of Africa, if the water comes from a tap in an urban area, it is safe to drink.

|

|

|

|

This area is called the "Lunar Landscape" Nothing grows for Miles Very Rough Country |

Typical Street in Swakopmund All the Buildings have this architecture |

The most significant water and wastewater problems are in the rural, and “peri-urban” areas. The peri-urban areas, or ‘informal settlements’, are areas adjacent to, or within, large formal communities. Poor people from the surrounding area settle in these previously vacant areas, hoping that the ‘city’ will provide them a better lifestyle. There is no municipal infrastructure in these areas, and no funding to provide it. Over time, these areas become permanent, but because there was no planning or organization, and because of the poor economic status of the residents, it is almost impossible to go in afterwards and provide services. These “informal settlements likely could not happen in Canada because of our very cold climate in the winter. The rural areas provide a different challenge. Many of the people in these areas are nomadic, changing the location of their settlements to follow crop rotation or animal herds. In the villages which are permanent, many water projects have failed because they have not taken into account the local social structure. Village women have traditionally been in charge of supplying water. The most successful projects have developed a central water facility, in consultation with the village people, and then turned the facility over to the village women to operate it. They manage the facility and charge for its use.

|

|

|

|

A local family lives in this house. They travel to this part of the desert each summer to pick a fruit (the outside looks like a green melon) |

This is a river near Swakopmund. It is dry most of the year, and when it runs (during rainstorms). There is some plant life here because of the water table. |

While safe drinking water is a huge issue, proper wastewater disposal is becoming a greater issue. While 50% of the population do not have access to safe drinking water, 75% do not have adequate sanitary conditions. As if that is not problem enough, AIDS is decimating the black youth. As many as one half of the black population under the age of 30 has AIDS.

The climatic and geologic conditions in Africa provide tremendous advantages for the installation of infrastructure as compared to Canada. As there is no frost, water and sewer mains only have to be as deep as required to keep them out of the way. Many of the roads in Swakopmund are constructed by grading a path through the sand, and then applying salt water and packing. The roads get as hard as pavement, and while they can get slippery when it rains, that happens only once or twice a year. Water Meters can be installed at the surface, and fire hydrants are simply a valve and coupling just below road surface in a small manhole.

|

|

|

|

Typical Fire Hydrant on a local street. (Marker in Background - Coupling just under cover on street) |

The main roads in Swakopmund are paved, but many are just graded with salt water applied. |

We have surprisingly many things in common. Even the sand, is surprisingly like our snow. It blows across the roads and builds up along fences and in the ditches. They use ‘sand fences’ to keep it back, and even use road graders to keep the roads and ditches clear.

I will never forget the experience of this meeting, or the professionalism of the members of the ESAR Council with whom I met. Assuring water supply and waste water treatment, both in terms of quantity and quality, and at an affordable price is our common goal. I am pleased that CWWA has had the opportunity to assist in the formation of these groups and look forward to working through the Association with our counterparts in southern Africa. I also must commend our Executive Director, Duncan Ellison, for the many volunteer hours he has dedicated to this project.

|

|

|

Swakopmund City Hall |

I was only in Africa for four days, but I did have time for some fun!!

|

|

|

|

One afternoon I went on a Quad Tour of the Dunes |

The Dunes were very HIGH - and Steep Quad'ing was very like skidooing |

|

|

|

I even tried Sand Boarding |